By: Timothy A. Raty; Sr. Regulatory Compliance Specialist

“mortgage insurance (1876) . . . 2. An agreement to provide money to

the lender if the mortgagor defaults on the mortgage payments. – Also

termed private mortgage insurance (PMI).” (INSURANCE, Black’s Law

Dictionary [10th ed. 2014])

Mortgage insurance, in one form or another, is a common attribute of mortgage loans within the United States. It is designed to protect creditors from losses if a borrower defaults on their loan and, more often than not, is paid for by borrowers either at consummation and/or as a part of their periodic mortgage payments. Due to this type of arrangement, Federal and state governments, Federal agencies, and government-sponsored enterprises (“GSE”) have enacted laws and rules stipulating when creditors can charge borrowers for mortgage insurance premiums – and for how long.

Prior to 1998, state laws were the chief regulators of these arrangements and their requirements varied greatly from each other. In 1998, the 105th Congress (R) and President William J. Clinton (D) passed “An Act to require automatic cancellation and notice of cancellation rights with respect to private mortgage insurance which is required as a condition for entering into a residential mortgage transaction . . .” (112 Stat 897 [1998])

Since then, this Act – the Homeowner’s Protection Act (12 U.S.C.A. §§ 4901 through 4910; “HPA”) – has become the standard in determining when private mortgage insurance (“PMI”) can be required in connection with certain mortgage transactions.[i] However, due to the federalized nature of the United States, there are nuances between Federal and State laws governing the same matter, leading to questions concerning when and to what extent such laws apply.

Also, while the GSEs have largely adopted the HPA as their standard, they have gone a “step further” and imposed cancellation requirements on transactions not subject to the HPA. Federal agencies, which provide “functional equivalents” of PMI, are not governed by the HPA and have their own termination requirements.

Altogether, determining when PMI must be cancelled or terminated transcends the straight-line of a sprint into an exercise in mental gymnastics.

The Homeowner’s Protection Act – Part I

Despite being the “standard” for PMI termination, the HPA is limited to only certain types of transactions.

First, the HPA’s PMI termination requirements only apply to “a residential mortgage transaction” (12 U.S.C.A. § 4902), which is defined as follows:

“The term ‘residential mortgage transaction’ means a transaction consummated on or after the date that is 1 year after July 29, 1998, in which a mortgage, deed of trust, purchase money security interest arising under an installment sales contract, or equivalent consensual security interest is created or retained against a single-family dwelling that is the principal residence of the mortgagor to finance the acquisition, initial construction, or refinancing of that dwelling.” (Ibid. § 4901[15])

The Federal Reserve Bank (“FRB”) provides a more detailed explanation as to how this definition applies (footnotes from the original source are added in brackets):

“The act applies primarily to residential mortgage transactions, defined as mortgage loan transactions consummated on or after July 29, 1999, the purpose of which is to finance the acquisition, initial construction, or refinancing [for purposes of this discussion, refinancing means the refinancing of a loan any portion of which is intended to provide financing for the acquisition or initial construction of a single-family dwelling that serves as a borrower’s primary residence] of a single-family dwelling that serves as a borrower’s primary residence [for purposes of this discussion, junior mortgages that provide financing for the acquisition, initial construction, or refinancing of a single-family dwelling that serves as a borrower’s primary residence are covered]. It also includes provisions relating to annual written disclosures for residential mortgages, defined as mortgages, loans, or other evidences of a security interest created with respect to a single-family dwelling that is the borrower’s primary residence. Condominiums, townhouses, and cooperative or mobile homes are considered single-family dwellings covered by the act.” (Consumer Compliance Handbook, 11/07, p. HOPA · 1; emphases in the original)

Thus, the following types of transactions are excluded (this is not an exhaustive list):

- Transactions involving a multi-unit dwelling or a vacant lot;

- Transactions involving a second home or an investment property which is not primarily occupied by the borrower;

- Refinances of loans which were not used to purchase or construct the borrower’s primary dwelling; and

- Renovation loans.

Second, state laws existing on or before January 2, 1998 which limit PMI coverage are only preempted by the HPA to the extent that they provide fewer protections to borrowers than the HPA. To wit:

“(A) In general

The provisions of this chapter do not supersede protected State laws, except to the extent that the protected State laws are inconsistent with any provision of this chapter, and then only to the extent of the inconsistency.

(B) Inconsistencies

A protected State law shall not be considered to be inconsistent with a provision of this chapter if the protected State law –

(i) requires termination of private mortgage insurance or other mortgage guaranty insurance –

(I) at a date earlier than as provided in this chapter; or

(II) when a mortgage principal balance is achieved that is higher than as provided in this chapter; or

(ii) requires disclosure of information –

(I) that provides more information than the information required by this chapter; or

(II) more often or at a date earlier than is required by this chapter.

(C) Protected State laws

For purposes of this paragraph, the term ‘protected State law’ means a State law –

(i) regarding any requirements relating to private mortgage insurance in connection with residential mortgage transactions;

(ii) that was enacted not later than 2 years after July 29, 1998; and

(iii) that is the law of a State that had in effect, on or before January 2, 1998, any State law described in clause (i).” (12 U.S.C.A. § 4908[a][2])

As summarized by the FRB:

“For residential mortgage transactions, the provisions of the act supersede state laws, except for those states that had PMI laws in effect as of January 2, 1998. Laws in these states are pre-empted only to the extent that they are less protective than the act. These states were permitted two years from the date of enactment (that is, until July 29, 2000) to amend their laws in light of the provisions of the act.” (Consumer Compliance Handbook, 01/06, p. HOPA · 6; emphases in the original)

According to Footnote 8 of Ibid., “Eight states (California, Colorado, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, and New York) had PMI laws in effect prior to January 2, 1998. See 144 Cong. Rec. 5, 432 (daily ed. July 14, 1998; statement by Rep. LaFalce).”

Statements within the Congressional Record indicate that there was some support for giving States more leeway in formulating their own PMI requirements and to make their own laws in the future which impose stricter requirements than the HPA, but ultimately, Congress agreed to only permit certain existing laws to be partially exempt.[ii]

Finally, the HPA only governs the cancellation or termination of “private mortgage insurance”, which is defined as “mortgage insurance other than mortgage insurance made available under the National Housing Act [12 U.S.C.A. § 1701 et seq.], Title 38, or Title V of the Housing Act of 1949 [42 U.S.C.A. § 1471 et seq.].” (12 U.S.C.A. § 4901[13]). Such a definition would exclude mortgage insurance (or its functional equivalent) provided by the FHA, VA, and RD.

Altogether, there are two basic types of “loopholes” in the HPA which permit additional PMI cancellation or termination requirements:

- Transactions subject to the HPA may be subject to more restrictive requirements under “protected State law”, which may cause PMI to be cancelled or terminated prior to the times that the HPA requires; and

- Transactions not subject to the HPA may be subject to PMI cancellation or termination requirements imposed by any State, Federal agency, or investor.

State Laws – Part II

At the time the HPA was enacted, there were approximately eight states who had their own PMI cancellation/termination laws, which could have been considered “protected State law” under 12 U.S.C.A. § 4908(a)(2). Since 1998, the laws of one have been repealed (Colorado) and one was added within the two-year timeframe set forth under Ibid. (Washington). Several of these states have laws which effectively mimic (if not defer to) the HPA (Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Missouri), while others essentially extend the HPA’s provisions to transactions not covered by the HPA and have provisions which can take precedence over the HPA in certain circumstances (California, Minnesota, New York, and Washington).

California – Substantially enacted in 1990 (see 1990 Cal. Legis. Serv. 1098), notable differences between California and the HPA include the following:

- Under California law, the loan must be “seasoned” by at least two years before cancellation (see Cal. Civ. Code § 2954.7[a][2]), while the HPA does not have a “seasoning” requirement.

- The loan must be secured by one-to-four unit, residential real property (see § 2954.7[a][3]) for California’s requirements to apply, while the HPA only applies to single unit dwellings.

- Termination under California law must occur when the unpaid principal balance owed is 75% or less of either:

- The sales price of the property at origination (provided the current fair market value is equal to or greater than the original appraised value); or

- The current fair market value as determined by a current appraisal (see § 2954.7[a][4])

While the “seasoning” requirement may be preempted by the HPA (which does not have a seasoning requirement and, in general, it preempts protected state law when it provides better protections to consumers), the extension of the termination requirements to two-to-four unit properties expands the termination requirements to loans not covered by the HPA.

The termination ratio of 75% could, in some cases, cause PMI to terminate at an earlier time than under the HPA, thus California’s requirements may supersede the HPA in certain circumstances – particularly if the current market value of the subject property substantially increases from its original market value.

Example # 1: Borrower purchases a home for $100,000, which is the same amount as the original market value for the home. The borrower does this with a fixed-rate mortgage loan. The borrower makes the scheduled payments, without any prepayments. Eventually, the borrower conducts an appraisal and determines that the current market value for the home is $120,000. The unpaid principal amount of the loan at this time is $90,000.

Under the HPA, the borrower cannot request cancellation until the principal balance reaches (or is scheduled to reach) 80% of the original value ($100,000 x 0.8, or $80,000). Under California law, the borrower can request cancellation when the unpaid principal balance reaches 75% of either the sales price ($100,000 x 0.75, or $75,000) or the current market value ($120,000 x 0.75, or $90,000).

Because the loan has reached the 75% threshold under California law before the 80% threshold under the HPA, California’s cancellation requirements may be satisfied, since they are “protected State law” and the “mortgage principal balance is achieved that is higher than as provided” under the HPA (12 U.S.C.A. § 4908[a][2][B][i][II])

Example # 2: The same example as above, except that the appraisal returns a current market value of $80,000 – which is the same amount of the remaining principal balance.

Because the current market value is less than the sales price, California’s “either” requirement cannot include the sales price (which can only be used if the current market value is equal to or greater than the original appraised value; in this case, it is $20,000 less), thus cancellation cannot occur until the unpaid principal balance reaches 75% of the current market value ($80,000 x 0.75, or $60,000).

However, under the HPA, cancellation may occur when the principal balance reaches (or is scheduled to reach) 80% of the original value ($100,000 x 0.8, or $80,000). Because California law does not result in a principal balance that is higher than the HPA, the borrower may cancel the PMI under the HPA.

There are other caveats to California’s law which makes the determination of cancellation or termination more complicated than simple comparison. For example, California’s termination requirements are satisfied if the loan is sold to “institutional third parties” (which includes FNMA, FHLMC, and GNMA) and such institutional third party’s PMI termination requirements are adhered to (see Cal. Civ. Code § 2954.7[c] & [d]). Because FNMA’s and FHLMC’s PMI termination requirements mimic those of the HPA (see FNMA 2019 Servicing Guide B-8.1-04 and FHLMC Single-Family Seller/Servicer Guide 8203), it is possible for a servicer to cancel PMI later than when it is permitted under California law (see Example # 1 above), but still do so in compliance with the law.

Connecticut – Substantially enacted in 1989 (see 1989 Conn. Legis. Serv. P.A. 89-95), Connecticut law sets forth disclosure requirements for PMI cancellation but, according to a letter dated October 2, 1998 by the Connecticut Insurance Department, such law did not require PMI to be terminated under State-specific conditions (see https://www.cga.ct.gov/PS98/rpt%5Colr%5Chtm/98-R-1157.htm).

The disclosure requirements require (inter alia) a disclosure of “what, if any, conditions the lender may release the borrower from” mortgage insurance (see Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. § 36a-726[a][2]). Notably, this requirement applies to a “first mortgage loan”, which only includes “one-to-four-family residential, owner-occupied real property” – thus covering subject properties (e.g. two-or-more unit properties) which would not be covered by the HPA (see Ibid. § 36a-725[1]).

Maryland – The remains of Maryland’s original PMI laws, which were substantively enacted in 1980 (see Md. Acts 1980, c. 22) completely defer to the HPA regarding the termination of PMI. It requires that certain financial institutions who hold “a first mortgage on residential property and a private mortgage insurance corporation partially insures the mortgage . . . shall eliminate all charges to the mortgagor or mortgage insurance premiums when the mortgage is reduced to the level at which the federal Homeowner’s Protection of 1998 requires termination of the private mortgage insurance insuring the mortgage.” (Md. Code Ann., Fin. Inst. §§ 5-508 & 9-903)

Massachusetts – Currently, Massachusetts’ does not have any cancellation/termination requirements, but loan servicers are specifically prohibited from “collecting private mortgage insurance beyond the date for which private mortgage insurance is no longer required.” (209 Mass. Code Regs. § 18.21A[1][b]) When private mortgage insurance is “no longer required” is left to Federal law and investor requirements.

Minnesota – The current requirements, which were enacted in 1999 after the HPA was passed, but within the two year “window” promulgated under 12 U.S.C.A. § 4908(a)(2)(C)(ii) (see 1999 Minn. Sess. Law Serv. ch. 151 [S.F. 1330]), permits PMI to be cancelled under certain conditions which are, notably, different than the conditions under the HPA:

- The cancellation requirements apply to a “residential mortgage loan”, which is defined to include “residential real property” and leaseholds in cooperatives (see § 47.207), the former of which is not defined. Thus, Minnesota’s cancellation requirements may apply to loans which are not covered by the HPA (e.g. two-or-more unit dwellings);

- When the unpaid principal balance of the mortgage is 80% or less than the current fair market value of the property (as opposed to the HPA’s original market value); and

- The loan must have been “seasoned” for at least 24 months (the HPA has no seasoning requirements).

(see Minn. Stat. Ann. § 47.207[2])

Also notable is the fact that these requirements include the following provision:

“Interpretation. Nothing in this section shall be deemed to be inconsistent with the federal Homeowner’s Protection Act of 1998, codified at United States Code, title 12, sections 4901 to 4910, within the meaning of ‘inconsistent’ as used in section 9 of that act, codified at United States Code, title 12, section 4908.”

Due to this, there are situations where PMI may be cancelled sooner under Minnesota law than under the HPA. This is particularly true in situations where the subject property has increased in value.

Example # 3: Borrower purchases a home for $100,000, which is the same amount as the original market value for the home. The borrower does this with a fixed-rate mortgage loan. The borrower makes the scheduled payments, without any prepayments. Eventually, the borrower conducts an appraisal and determines that the current market value for the home is $120,000. The unpaid principal amount of the loan at this time is $90,000.

Under the HPA, the borrower may request cancellation when the outstanding balance is 80% of the original value ($100,000 x 0.8, or $80,000). However, under Minnesota law, PMI may be cancelled when the outstanding balance reaches 80% of the current value ($120,000 x 0.8, or $96,000). Because protected State law supersedes the HPA when it is more favorable to the consumer, the borrower may request that PMI be cancelled.

Conversely, if the appraisal determines that the current market value for the home is $95,000, then the borrower must wait until the outstanding principal balance either reaches or is scheduled to reach $80,000, since PMI under Minnesota law cannot be cancelled until a later time (when the balance reaches $95,000 x 0.8, or $76,000).

Missouri – Missouri law has two sections governing PMI within the same context as the HPA, but neither promulgate any cancellation or termination requirements. One limits the amount of mortgage insurance to 103% or less “of the fair market value of the authorized real estate security at the time that the loan is made if secured by a first lien” (Mo. Ann. Stat. § 443.415). The other authorizes a separate charge for mortgage insurance for second mortgage loans (see Ibid. § 408.233[2]).

New York – New York’s PMI cancellation requirements were enacted in 1984 (see L. 1984, c. 367, § 1) and are, arguably, the ones which provide the most contrast with the HPA. This is due, in large part, to the fact that N.Y. Ins. Law § 6503 bases the criteria for when PMI must be terminated (“terminated” as in the borrower may no longer make premium payments for it) primarily on the lien status of the loan. To wit:

- For primary lien loans, if the loan is not made pursuant to “the state of New York mortgage agency’s forward commitment program” (e. SONYMA forward commitment loans), PMI must be terminated when the unpaid principal balance is 75% or less of the subject real estate’s original appraised value (see Ibid. § 6503[d]);

- For primary lien, SONYMA forward commitment loans, PMI must be terminated (under statutory law) when the unpaid principal balance is 60% or less of the original fair market value of the subject real estate. Note that while this is statutorily required, SONYMA currently requires PMI to be terminated once the current unpaid principal balance is 80% or less of the original value of the property (see § 6503[e] and https://hcr.ny.gov/sonyma-borrower-faqs);

- For any junior lien loan, PMI is terminated once the unpaid principal balance, combined with any other existing mortgage loan amounts at the time the junior lien loan is made, is less than 60% of the original fair market value of the subject real estate (see § 6503[f]).

Similar to California and Minnesota, there are cases where PMI will need to be terminated sooner under New York law than under the HPA. In contrast to California and Minnesota, New York’s laws apply to the termination – rather than borrower-initiated cancellation – of PMI.

Example # 4: Borrower purchases a home for $100,000, which is the same amount as the original market value for the home. The borrower does this with a fixed-rate, primary lien mortgage loan. The borrower makes the scheduled payments, without any prepayments and, eventually, the unpaid principal amount of the loan is reduced to $78,000.

Under the HPA, PMI termination occurs when unpaid balance is scheduled to reach 78% of the lesser of the sales price or the original appraised value ($100,000 x .78, or $78,000). Under New York’s requirements, termination occurs when the unpaid balance actually reaches 75% or less of the original appraised value ($100,000 x .75, or $75,000). In this example, PMI would be terminated sooner under the HPA, thus it preempts New York’s protected state law.

Example # 5: The same as Example # 4, except that when the unpaid principal amount of the loan reached $90,000, the borrower made a $15,000 prepayment. Due to this prepayment, PMI must be terminated on the loan, because the actual unpaid principal balance of $75,000 occurs at an earlier time than when the unpaid principal balance was scheduled to reach $78,000, New York’s protected state law takes precedence over the HPA.

Washington – Washington’s PMI cancellation laws were enacted on April 1, 1998 (see 1998 Wash. Legis. Serv. ch. 255) and took effect on July 1, 1998—three days after the HPA was signed into law. While again similar to the HPA, Washington’s cancellation requirements have a few, notable nuances:

- The requirements apply to a “residential mortgage transaction”, which is defined to include 1-to-4 unit, residential real properties (see Wash. Rev. Code Ann. § 61.10.010[3]);

- There are “seasoning” requirements, as opposed to the HPA (see § 61.10.030[1][b]);

- While the cancellation requirements are similar to those of the HPA, they do require the outstanding principal balance of the loan to be both 80% or less of the current fair market value of the property and less than 80% of the original appraised value (or sales price, if lesser than the original appraised value in a purchase transaction; see § 61.10.030[1][c]). This contrasts with the HPA, which specifically states that the outstanding balance is ignored in determining the “cancellation date” (see 12 U.S.C.A. § 4901[2])

Similar to New York, Washington’s cancellation requirements will supersede those of the HPA mainly when the borrower makes prepayments on the loan. It also extends HPA-like cancellation requirements to mortgage loans which are not covered by the HPA.

GSEs – Part III

No special exemption from the HPA is applied to the GSEs. On the contrary, the HPA states the following:

“The provisions of this chapter shall supersede any conflicting provision contained in any agreement relating to the servicing of a residential mortgage loan entered into by the Federal National Mortgage Association, the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, or any private investor or note holder (or any successors thereto).” (12 U.S.C.A. § 4908[b])

Since 1999, the GSEs have conformed their PMI cancellation/termination requirements to mirror those of the HPA, for single-family, borrower-occupied dwellings (see FNMA Ann. 99-06 and FHLMC Bull. 99-4). However, the GSEs also require additional steps to be taken before PMI may be cancelled or terminated. Some of these steps include verifying the current value of the property and requiring that the borrower’s payments are current (see FNMA 2019 Servicing Guide B-8.1-04 and FHLMC Single-Family Seller/Servicer Guide ch. 8203.2 – 8203.8).

Despite these extra steps, servicers must still cancel or terminate PMI when required by the HPA, even if doing so does not comply with the GSEs requirements. This was emphasized by the CFPB in 2015, as follows:

“Many mortgage loans are owned by Government-Sponsored Enterprises, or GSEs, such as Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac. These and other loan investors often create their own internal PMI cancellation guidelines that may include PMI cancellation provisions beyond those that the HPA provides.

The CFPB cautions servicers to implement investor guidelines in a way that does not lead them to violate consumer financial law. Both the HPA and some investor requirements contain similar LTV thresholds for PMI cancellation and termination, and use similar measures of the property’s value. Servicers should nonetheless remember that investor guidelines cannot restrict the PMI cancellation and termination rights that the HPA provides to borrowers.” (CFPB Bulletin 2015-03, available at: https://www.consumerfinance.gov/policy-compliance/guidance/mortserv/; emphasis in the original)

In addition to requirements imposed upon loans subject to the HPA, the GSEs also impose PMI cancellation/termination requirements for loans secured by two-to-four unit dwellings, second homes, and investment homes (which, in most cases, would not be covered by the HPA). The GSEs requirements differ from each other, as follows:

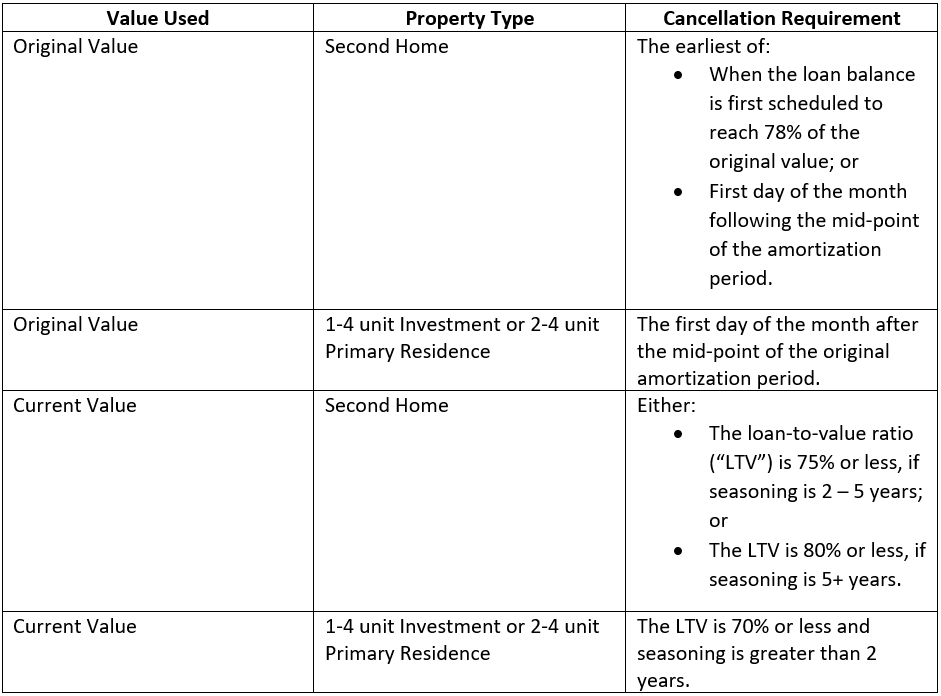

FNMA – There are two types of borrower-initiated cancellations of PMI, where either the original or current value of the subject property is used to determine when PMI may be cancelled. The following table illustrates the general borrower-initiated cancellation requirements for loans which would not be subject to the HPA:

Regarding automatic termination, PMI coverage is terminated for loans secured by a second home when either: (i) the loan balance is first scheduled to reach 78% of the original value of the subject property; or (ii) the first day of the month following mid-point of amortization. For loans secured by one-to-four unit investment properties or two-to-four unit principal residences, PMI is terminated on the first day of the month following the mid-point of the original amortization period.

FHLMC – Mortgage loans are divided into two types. An “HPA Mortgage” is defined as “a 1-unit Primary Residence Mortgage with mortgage insurance originated on or after the HPA Effective Date” and, interestingly, “any second home Mortgage (as defined in Section 4201.15) with mortgage insurance” (FHLMC Single-Family Seller/Servicer Guide ch. 8203.1). A “Non-HPA Mortgage” is defined as “any Home Mortgage with mortgage insurance, originated on or after the HPA Effective Date” (Ibid.)

Similar to FNMA, FHLMC has two types of borrower-initiated cancellation for Non-HPA Mortgages, which are based upon either the original or current value of the subject property; unlike FNMA, however, FHLMC does not have separate criteria for separate property types.

Based on the original value of the subject property, PMI may be cancelled when the LTV ratio is 65% or less. Based on the current value, PMI may be cancelled when the LTV ratio is 65% or less, with either: (i) two years of seasoning; or (ii) substantial improvements made to the subject property, causing its market value to increase since the date of the promissory note.

Automatic termination of PMI is not authorized for Non-HPA Mortgages (see Ibid. ch. 8203.4).

Federal Agencies – Part IV

Conceptually, mortgage insurance (or its functional equivalent) provided by a government agency cannot be considered “private.” This is reflected in the definition of “private mortgage insurance” under the HPA, which states that such term “means mortgage insurance other than mortgage insurance made available under the National Housing Act, Title 38, or Title V of the Housing Act of 1949.” (12 U.S.C.A. § 4901[13]) It is further reflected in the fact that public mortgage insurance is normally excluded under State laws governing the cancellation of private mortgage insurance (e.g., see Cal. Civ. Code § 2954.6[f] and Wash. Rev. Code Ann. § 61.10.030[e][3][a]).

Nevertheless, FHA, VA, and RD have their own rules governing the cancellation/termination of the mortgage insurance (or its functional equivalent) that they provide. For the sake of simplicity, “public mortgage insurance” refers to either mortgage insurance or its functional equivalent.

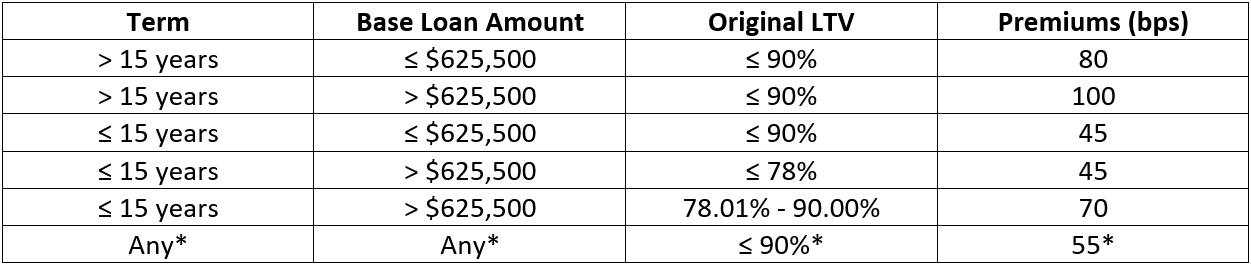

FHA – For Title II, Single-Family FHA loans, there are cancellation rules governing loans that are closed on or after January 1, 2001 and have a case assignment dated before June 3, 2013. For such loans, public mortgage insurance is automatically cancelled when certain loan-to-value (“LTV”) ratios are (generally) scheduled to be reached (which ratios excludes any financed upfront mortgage insurance premiums). These ratios will depend on various factors, such as when the loan was closed or assigned a case number, loan term, and what the original LTV ratio was for the loan. Most of the cancellation-point LTV ratios are 78% of the lesser of the initial sales price or initial appraised value, though the ratios are less than 90% for short term loans (15 years or less) which were closed on or after January 1, 2001 and have a case number assigned before July 14, 2008 (see FHA Single Family Handbook 4000.1 Pt. III.A.1.k[ii] for details).

A borrower may, however, request the cancellation of their annual premiums before the scheduled LTV ratio is reached, if such LTV ratio is actually reached due to the borrower’s prepayments (but no sooner than five years from closing, except for loans with 15-year terms) and if the borrower has not been more than thirty days delinquent during the previous twelve months (see Ibid. Pt. III.A.1.k[ii][E]).

For most other Title II Single Family FHA loans, public mortgage insurance cancellation/termination requirements are outlined in FHA Single Family Handbook 4000.1 App. 1.0. Generally, public mortgage insurance cannot be cancelled/terminated at all during the life of the loan. There are, however, a few loans where it may be cancelled/terminated eleven years into the loan term. These are as follows:

*Only applies to streamline or simple refinances of a previous mortgage endorsed on or before May 31, 2009.

Please note that while upfront mortgage insurance premiums are required for all of these loans, annual premiums are not required for Hawaiian Home Lands loans (aka Section 247 loans).

VA – While not strictly mortgage insurance, the Federal government’s guaranty of certain loans extended to veterans is considered a “functional equivalent” of mortgage insurance under some laws (e.g., see 12 C.F.R. Pt. 1026, Supp. I, Paragraph 37[c]1[][i][C] – 1). However, the guaranty is never cancelled throughout the life of the loan, short of bad actions (e.g., fraud) on the parts of certain parties (see 38 C.F.R. § 36.4328 for details).

RD – Like VA loans, the RD does not provide mortgage insurance, but rather a guaranty, which is also considered a “functional equivalent” of mortgage insurance under some laws (e.g., see Ibid.). Also like the VA’s guaranty, the RD’s guaranty is never cancelled during the life of the loan, but continues “until termination of the Loan Note Guarantee.” (RD HB-1-3555 ch. 16.5[H]; see also 7 C.F.R. § 3555.107[h]).

Conclusion

Determining when PMI can or must be cancelled/terminated is complex and will differ on a loan-to-loan basis. To help navigate through this, the tables in the following link provide a summary of most of the requirements’ application to specific types of loans. Please note that these tables do not reflect Federal agency requirements (since such agencies either provide their own charts or have too simplistic rules), does not reflect mid-point termination rules (unless illustrated otherwise), and contains only a base summary of the cancellation/termination requirements. Nevertheless, we hope you find it to be a useful map through this complex maze.

Mortgage Insurance Cancellation or Termination Requirements Tables

______________________________________________________________________

[i] An in-depth analysis of the Homeowner’s Protection Act (12 U.S.C.A. §§ 4901 through 4910; “HPA”) has been provided by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (“CFPB”) and is available on their website (https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-provides-guidance-about-private-mortgage-insurance-cancellation-and-termination/). The Federal Reserve Board (“FRB”) also provides an older, but still valid, analysis (available directly at: https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/supmanual/cch/hpa.pdf).

[ii] “With regard to State preemption, again, I much preferred the House version. At least in this case the bill does protect State PMI cancellation and consumer laws in effect prior to January 2, 1998, and provides those States, eight of them, 2 years to revise and amend their laws: California, Minnesota, New York, Colorado, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Missouri.

I would have strongly preferred that the bill simply respect the rights of all States to enact stronger cancellation and disclosure laws, or had allowed the eight States with laws on the books to amend their laws without limitation. Nonetheless, I am pleased that we are now protecting stronger State consumer laws in States like New York, where they already do exist.” (144 Cong. Rec. H5428-02 [July 14, 1998])